My toes know it’s cold outside. My nose knows too. And my ear. Our thin nylon tent holds little warmth. Last night the mercury fell to –2°C in the mallee. Cold on the extremities, but not cold in the extreme. Cold in the extreme? Last seen, winter ’82.

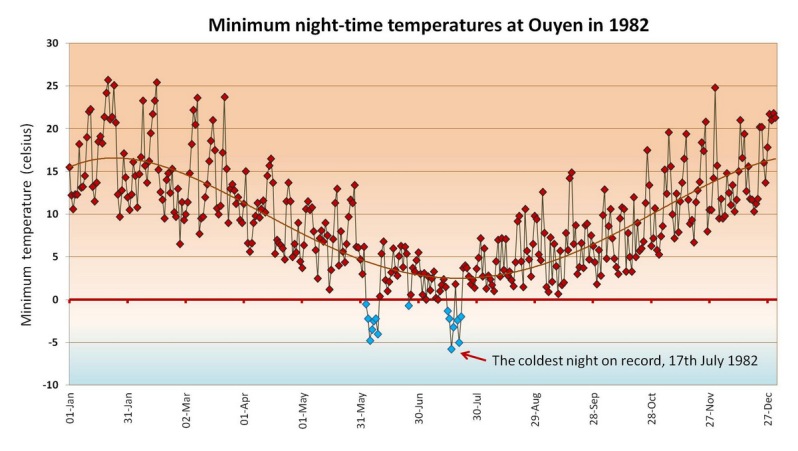

Every winter, the small town of Ouyen – a grain silo, roadhouse, general store and little more – gets about 18 frosts. Most years, the coldest night is a chilly –1°C. Thirty two years ago, the mercury plummeted.

In the early 1980s, Australia was crippled by drought. Between dust storms and bush fires, El Nino brought clear days and cold nights. Friday morning, June 4th 1982 was colder than usual: –2.2°C. The next five nights were colder again. Saturday hit a record low: –4.8°C. Pity the publican hosing the footpath outside the Victoria Hotel.

A month later, the frosts returned: –2.2°, –5.8°, –3.2°, –2.4°, –5.0° and –2.0°C, night after night. In Ouyen, –5.8°C isn’t just cold on the extremities. It’s cold in the extreme and extremely rare. Since records began, it has happened just once, on 17th July 1982.

Ouyen isn’t the coldest place in the mallee. In June ’82, the weather station outside the old ranger’s house at Wyperfeld National Park hit –5°, –7°, –8°, –7°, –6° and –5°C. In the cold snap of July, the mercury sunk to a record low, –8°C. The next day, sky clear once more, things mostly went back to normal. ‘Back to normal’ and ‘same as it ever was’ are two very different things. Exposed to extreme cold, something snapped in the mallee. One observer wrote,

The impact on the vegetation was dramatic. Thousands of hectares of mallee scrub and heathland were devastated, especially in the interdune swales.

The warm thermometer

The standard technique for measuring temperature is to hang a minimum-maximum thermometer in a white slatted box, 1 to 2 m above the ground. The box is called a Stevenson Screen; named after Thomas Stevenson, a Scottish lighthouse designer (that’s an exclusive niche, I hear you say) who designed the prototype in 1864.

On winter nights it’s warmer inside the box than out. Cold air rolls past the screen to the lowest point in the landscape. Down past the ankles, to the frost hollows, the swales, between the dunes of mallee sand. Nobody knows how cold it got in the mallee swales in winter ‘82. One researcher estimated –13°C. Whatever the number, the drought-stricken plants hadn’t felt that cold for a long, long time.

The iceberg in the ice-chest

Have you ever put a lettuce in the freezer? Gourmet salad begone. As the water in a lettuce leaf freezes and expands, the cell walls break, the cells die, and your defrosted iceberg turns to sludge; to something you could drizzle across a salad. Cold-dwelling plants can’t be so hyper-sensitive. They sit in the freezer every winter.

Desert Banksia, Banksia ornata, is a short stocky shrub, 2-3 m tall. It grows across the southern mallee from the low swales to high dune crests. The fat yellow honeysuckle flowers feed pygmy possums, honey-eaters, moths and bees.

Curious scientists once put Banksia ornata seedlings in the deep freeze, at –20°C every night for a week. On the seventh day, they thawed and sliced each leaf, stained the cells with Evans Blue, and inspected the sections under a microscope. Less than 5% of the cells showed any damage. The researchers reported calmly:

… foliage of this species appears to be remarkably resistant to repeated freezing and thawing…

Yet the cold snap of ‘82 broke the banksias. Desert Banksias and other species died across huge areas.

With the exception of sporadic survivors, all adult [Banksia] ornata in frost-affected swales were eliminated.(O’Brien et al. 1986)

And they never came back

Fire, not frost, fuels the life cycle of Banksia ornata. Hot fires kill plants and warm the resin that binds closed their seed cones. The heated resin melts, the cones open, seeds fall to the ground, and new seedlings grow.

The frosts of ‘82 failed to melt that resinous glue. Plants died but the cones stayed closed. Few seeds fell to the ground and fewer seedlings regenerated. The Banksias disappeared from the swales; their evidence consumed by fires that later burnt the dead, frost-bitten plants.

In many parts of the Park, the only surviving adult [Banksia] specimens are now located on dune crests and upper dune slopes above the level affected by the frosts.(O’Brien et al. 1986)

The white witch stays

Could that extreme event, that super-cold frost, occur again in a world of global warming? As temperatures rise, frosts will surely fall. Logical as that may seem, it isn’t happening. At least, not yet.

Steven Crimp and colleagues from CSIRO studied weather records from 1960 to 2011 from across south-east Australia. In a new paper, they discovered that frosts are becoming more common, not less common, in inland areas below 100 m altitude; an enormous region that includes the Mallee and much of north-west Victoria and south-west NSW.

Surprisingly, average temperatures are rising and frosts are getting more common. More surprising still, the frost season is getting longer.

Consistent across southern Australia is a later cessation of frosts, with some areas of southeastern Australia experiencing the last frost an average 4 weeks later than in the 1960s.(Crimp et al. 2014)

Crimp and colleagues weren’t concerned about Banksias. They worry about wheat. Compared to a Banksia seedling, wheat is a wimp. Like a lettuce in a freezer, a young ear of grain can be ruined by a single night of wild frost. Not surprisingly:

This apparent ‘paradox’ of minimum temperature warming but increasing frost extremes is of significant concern to various agricultural industries.(Crimp et al. 2014)

The alarming paradox has a cause. Atmospheric circulation systems are moving. As high pressure systems move south, they create clear, cold and frosty nights in the mallee. Which is why it’s so cold on the extremities in our thin nylon tent.

Climate change provides no respite from cold nights in the mallee. But what of nights ‘cold in the extreme’? Will global warming mean the end of –13°C in a low mallee swale? Truth is, we don’t know.

The story of climate change is partly about changes in average temperatures. But it’s equally a story about changes in extremes. About the increasing frequency of unexpectedly severe events. The rare events that change ecosystems. Events that kill desert shrubs and make bats and birds drop from trees. Events that are increasing not declining.

Frost-bitten wounds

There’s a strange disconnect in an altered landscape. Perched on a mallee dune, resting from our walk, we gaze upon one of the most beautiful, natural landscapes I know. A landscape my brain compulsively re-populates with banksias. A species decimated not by persecution, human folly or greed, but by a change in the weather. What could be more natural? A short bout of extreme temperature, a few cold nights in a thin nylon tent.

As we wander, I contemplate the future. How will naturalists and ecologists in the year 2100 think about ecosystems altered by a ‘change in the weather’? Will they, like me, repopulate the view with vanished species? And what new words will they use to describe a world transformed by climate change? Will old terms like balance, equilibrium, intact, local provenance and climax be abandoned as archaic, redundant, quaint?

Or, accustomed to constant change, will they behold the most beautiful landscapes they know? And sit and rest, and enjoy the view that we left behind?

Postscript

I have posted a series of photos that show the aftermath of the 1982 frosts in a later post, Bringing back the dead with old ecology photos.

Acknowledgements

All of the photos in the post are from the web. The top photo of the tent in frost is from the Camp in Mudgee website.

Further reading

Cheal, D. (1997). Survival of desert banksia Banksia ornata seed in detached cones. Victorian Naturalist 114(4), 190-191. [full article].

Crimp, S., Bakar, K.S., Kokic, P., Jin, H., Nicholls, N. & Howden, M. (2014). Bayesian space–time model to analyse frost risk for agriculture in Southeast Australia. International Journal of Climatology, early view. GRDC (2014). Frost risk on the rise despite warmer climate [web page].

O’Brien, T., Forbes, C. & Jobe, L. (1986). The impact of severe frost on Mallee eucalypts, Banksia ornata, and Leptospermum coriaceum at Wyperfeld National Park. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 98, 121-31. [pdf of full article]

O’Brien, T. (1989). The impact of severe frost. In: Mediterranean Landscapes in Australia, Mallee Ecosystems and Their Management, pp. 181-188. (Edited by J.C. Noble & R.A. Bradstock). CSIRO, East Melbourne. [pdf of full article]

Hi Ian

Great post and a very interesting story. I’ve done a little work on frosts and am gearing up to do some more (frosts are more frequent here in NZ!) and thought I might throw in my two cents.

That is very interesting that climate change is causing frosts to be more frequent in the mallee and in other adjacent low-lying areas. There is also evidence from elsewhere that frost impacts on plants are becoming more severe even in areas where frost frequency is declining (see for example: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02712.x/abstract). Warmer temperatures have led to earlier bud break, rendering some species more susceptible to late spring frosts. Higher [CO2] will also likely lead to increased frost damage (see http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01499.x/abstract).

The other thought that I had was that there might be another mechanism underpinning the death of Banksia in the mallee. There are two main ways by which frost impacts plants; 1) ice crystallization causing rupture of cells in leaves; and 2) hydraulic failure due to freeze-thaw embolisms (see this great video for an explanation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d260CmZoxj8&list=UUeiYXex_fwgYDonaTcSIk6w#t=65). O’Brien et al. show that the leaves of Banksia are highly frost resistant, so I wonder if it is hydraulic failure due to freeze-thaw embolism that caused deaths in this species? How does the wood density of Banksia compare with the Leptospermum and eucalypts? Lower wood density would be consistent with lower resistance to freeze-thaw embolism.

Finally, I believe that plants that are already drought-stressed are more susceptible to freeze-thaw cavitation, so the severe drought probably played a role in these impacts too (can’t put my hand on the refs right now, but can dig them out if you are interested.

Thanks again for a great blog on something I’m really intrigued by – how plants are affected by extreme climatic events. Cheers Tim

Hi Tim, thanks very much for a great comment. I look forward to reading the papers. I don’t know how dense the Banksia wood is unfortunately. I hadn’t thought of the embolism problem, but that makes lots of sense. I strongly recommend that everyone watch the fantastic video that Tim linked to above; it’s short, really informative and great fun to watch, with simple cartoon graphics. Cheers Ian

No worries at all, Ian. It is a great video, isn’t it? It was based on the paper by Amy Zanne et al. in Nature: http://phylodiversity.net/azanne/papers/nature12872.pdf

See here for a news report: http://mediarelations.gwu.edu/study-how-plants-evolved-weather-cold

Hi Tim, thanks gain for the great links, I look forward to reading them. Best wishes Ian

Thanks Ian for another great post and thanks Tim for his thoughts also. More food for thought on the impacts of climate change. I for one had not considered extreme cold as being a concern! Keep the blogs coming.

Thanks Steven, I’m glad you liked it, best wishes Ian

I suspect climate change will involve “untempered” temperature ranges – increasing fluctuations between lower minimums and higher maximums, even if the mean changes only slightly. The prediction of means, by itself, never tells the whole story.

Hi Desert Dancer, thanks for writing in, you make a great point. We often give far too much attention to means rather than focusing on the amount of variability. Best wishes Ian

Ouyen used to be the site of the World Custard Slice Championships for many years I think this deep cold may be caused by them giving up that honour!

Hi Max, perhaps it was their secret ingredient, like using a cold marble bench top 🙂 best wishes Ian

Seriously though Ian I do have an item to share. In 1982 on our farm on the south coast of NSW we were trying to grow a commercial crop of South African Proteas on a block of sandy swale near a lake edge. We recorded -4 deg one night (though this was recorded in a Stevenson screen too so real temp may have been much lower) which due to a sea mist hanging over the site, that dispelled rapidly as the sun came up, saw the temperature go extremely quickly from below zero to +1 and onwards. The effect was spectacular most of the young seedlings literally burst their stems a few mm above ground level and we lost the entire crop. Cells rupturing is real and nasty to see!

Hi Moved to this region from Far East Gippsland ~1000mm rainfall to ~350 mm, just after decadal drought so not a plant in sight, only red sand. Big shock. Also big shock how dead this area was in terms of vegetation removed (>80% which doesn’t deter locals from further clearing) and mammals extinct. Combined with salinity this area is fundamentally dying. Must have been spoilt in EG. Bigger shock to come after 1 in 100 year floods. Summer 2013-2014 severe heat, often thermometer reading >45 degrees, and put on ground >50.

I’m near Nyah area over near Murray, but have visited Ouyen a bit, and conversations with locals confirmed my view that the official BOM sites don’t reflect the readings in the area, with less than 45 official readings on days when we were all heading towards 50. Anyhow that was last Summer so if El Nino is confirmed, this Summer will actually be worse. I have to say that a couple of nights ago when you reported the frost was nothing here compared to tonight, although there have been some very cold nights and I have noticed a number of frosts.

I am upgrading quals and tried to do a study which could lead to insights into biological crusts, succession and evaporation at Lake Tyrrell after THAT summer. But of course it teamed down and I was stuck in the mud and the lichens seemed to be in very poor condition! So other than the evaporation issue which it is clear to me is a huge driver in Australia, much underestimated, although Raupach et al from CSIRO noted that it is influential in northern Australia whilst rainfall is the driver in southern Australia, seasonality is stark here, really stark. I suspect the lichen crusts thrive in summer and the mosses thrive in winter and they have it all arranged. Evaporation of retained soil moisture is severe in Summer and as you point out the frosts can also be severe. However in East Gippsland frosts lasted well through the morning, which they don’t here, and it was so cold in the Winter that Currawongs migrated down to the coast where I lived, so you always knew when Winter arrived.

I personally think the mallee in northern Vic verges on being classed arid rather than semi-arid. With regard to climate change I looked at the 80 year forecast on Climate Wizard which uses IPCC I think, and there appears to be a change for Australian arid regions which means increased temperatures but also increased rainfall, but that ceases around about the Victorian mallee. This may therefore be a transitional climatic zone of some sort, which I guess means semi-arid rather than desert. The joys of such a semi-arid transition zone are thus cooking in summer and freezing in winter, with very little moisture. Therefore frosts and dew are essential to plant survival, but as with xeromorphic adaptations to heat, there is only so much tolerance ability.

So with increasing extremises, particularly without the 80 year increase in precipitation, but with the reduced vegetation cover and salinity, means a bit of a horror ahead for this region. In the meantime the call is for the regional increase in human population to occur here, in spite of the existing stresses on the Murray. There is no endemic water whatsoever here, all water comes from external streams and limited rainfall, so generally overnight dews and frosts are a good thing. Soil carbon is largely derived from biological crusts in arid areas, and these must have soil moisture to photosynthesize. The disturbance to these from grazing etc. given that >60% of Australia is rangelands with limited soil C dependent on biological crusts is a national catastrophe. What is really likely here is increased desertification, but although we are a signatory to the convention, apparently we feel the problem is “somewhere else”. The truth is that most of the population in Australia is somewhere else than the main zone and there is little concern for these regions in the mainstream. It’s a little difficult to have a convincing argument about climate change though if one is literally shivering!

Thanks very much for writing in. I can fully believe that moving from East Gippsland to Nyah would be a big shock to the senses, especially in summer. I hope you get a chance to return to a study of biological soil crusts as they are so important in semi-arid and arid areas. Best wishes Ian

You’ll have to forgive me for blowing my own trumpet, but I don’t often get feedback this enthusiastic from the interwebs. Thanks Tim!

Seriously good blog! FWIW (re Tim’s comment at top) farmers tend to know that frosts during drought have more severe impact than during wetter years

Hi Tim. I’m sure they do! Many decades experience of seasonal changes + having your livelihood depend on it would sure sharpen the observational skills.

If you are interested here’s a paper that touches on some of the mechanisms involved: http://www.plantphysiol.org/content/140/1/374.full Cheers Tim

Great work, Ian. Thanks for bringing this topic to the forefront of people’s minds. I’m going to present some related work on shrub freezing resistance at the ESA conference in Alice Springs in a few weeks – about how alpine shrubs can/cannot handle freezing temperatures once being released from snow in spring. It’s a similar idea from arid zones where the ‘comfortable’ conditions suddenly get interrupted by a big frost. One day I’d like to compare alpine and arid zone plant freezing resistance (especially among phylogenetically related species), and also test their susceptibility to drought…

Hi Susanna, thank for commenting. It’s fascinating to think that alpine and arid zone species – things we think of as being at opposite ends of the climatic spectrum – both have to deal with really similar temperature extremes in cold weather. The arid zone species also have to deal with extreme day time high temperatures as well! They are amazingly hardy, best wishes Ian

Reblogged this on Environmental change: an Adelaide view and commented:

Interesting changes in frostiness (and plant responses) as a result of overal warming.

Hi John, thanks very much for the blog link, I appreciate it. Best wishes Ian

As we are experiencing record lows on the Atlantic Coast of North America, the experience you’re sharing here is particularly salient. A lot to unpack.